Check out the Premium Anatomy course to see the full version of this video and all other Anatomy videos.

Introducing the Spine

The spine is literally the backbone of the body. It holds the torso together and moves it around.

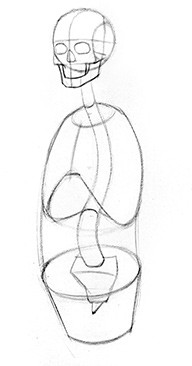

We’re going to start our study of the skeleton with the spine. The spine is the connection between the 3 major masses: the head, ribcage and pelvis. And it’s wedged between 2 butt cheeks.

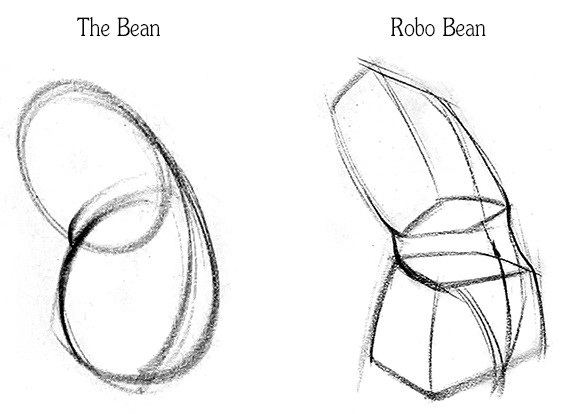

When constructing the figure, it’s common to start with these 3 masses, before adding the limbs. Remember how in the figure drawing course we used The Bean and Robo Bean to quickly establish the torso? The bean was a simple way of establishing the gesture of the torso using simple shapes. The robo bean added more structure to the bean to describe its orientation in space.

"I can’t even see the spine. Why do we study it?"

Here’s the deal with the spine. It places the rib cage, the pelvis, and the skull wherever they happen to be, and they can’t go anywhere the spine doesn't let them. They inherit the spine’s limitations. If we want to construct a torso in any pose, we need to understand the spine. Let’s do it.

Big Structure of the Spine

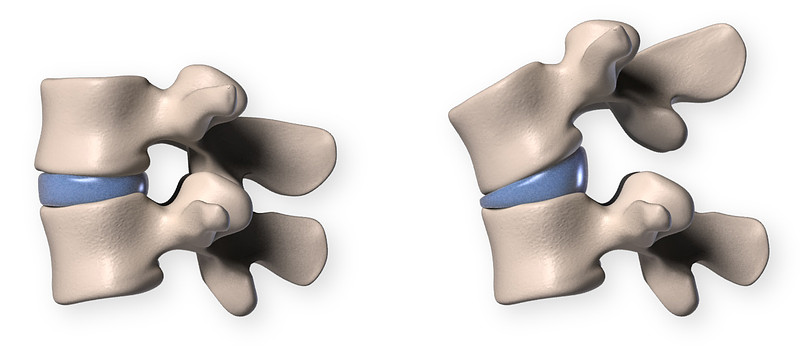

The spine is strong enough to support the weight of the upper body, yet flexible enough to move. It’s composed of 24 individual vertebrae - hard bones that give the spine its strength. The vertebrae have flexible cartilaginous discs between them, that allow the spine to move as a single line. Each plane moves only a little, but they add up to a lot. Like string of beads. Every little movement contributes to a graceful curve.

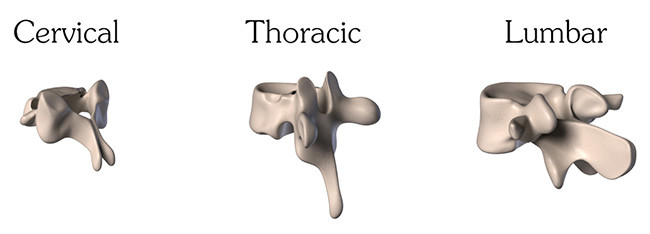

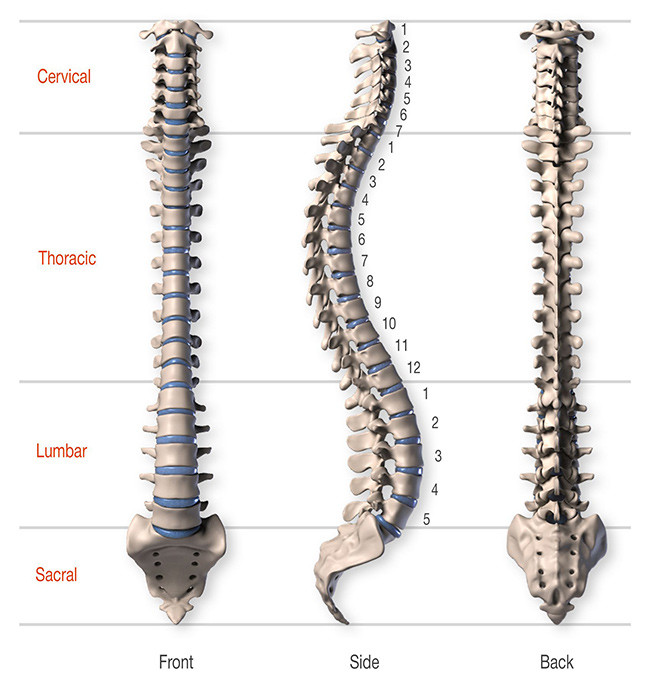

There are 4 sections to the spine. The Cervical section of the neck consists of 7 vertebrae. The Thoracic section of the ribcage has 12 vertebrae, one for each rib. The Lumbar section of the lower back has 5 vertebrae. The fourth section is technically considered as 2 separate sections, but I’m going to combine them - the sacrum and coccyx, which is the tailbone. Let's call this the Sacral section.

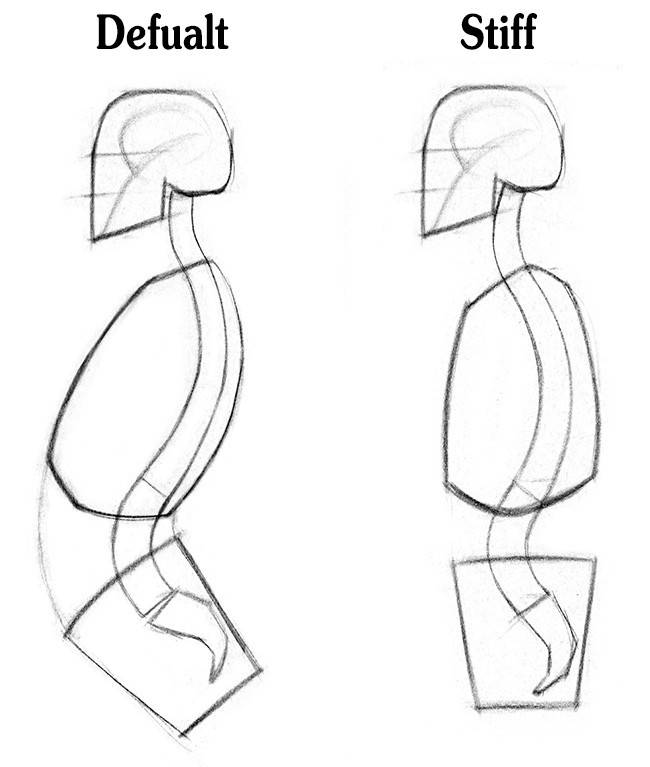

The sections give the spine a 4-arch curve. If the spine were a straight line, it would be strong, but rigid. This 4 arch curve gives better flexibility for shock absorption and aids in balance. And it’s the framework for the posture of the body.

The cervical curve is the least curvy - it’s almost a straight line. But, it does have a very subtle forward curve. The thoracic curve is longest, and more curvy than the cervical section. It curves backward and aligns with the shape of the ribcage. The lumbar section curves forward and is even more curvey. The Sacral curve is the most curvey of all the sections. So, as you can see the curves get progressively curvier as they go down the spine.

Common Structure of the Vertebrae

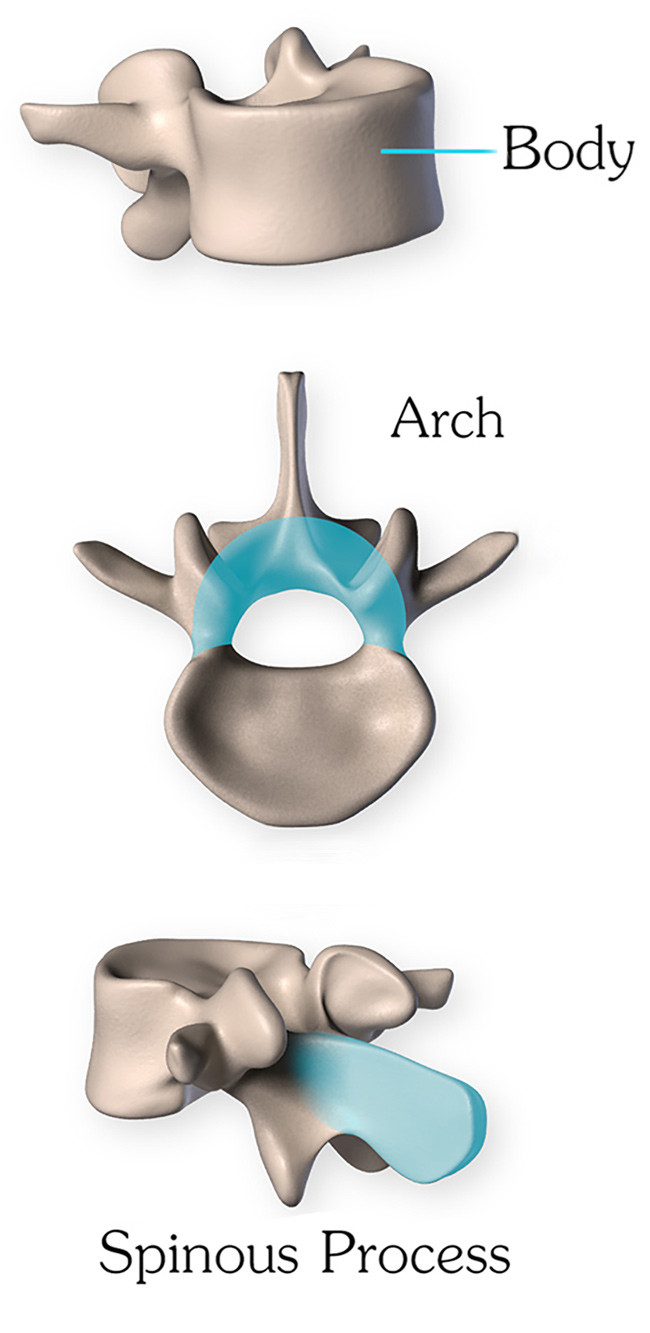

The vertebrae of each section have slightly different structures, some for strength, some for flexibility. However all the vertebrae, share the same common components.

Each has a thick disk-like Body, which connects to the neighboring vertebra with a squishy little pillow, forming the main joint of the spine.

On the back of the body is a u-shaped Arch, creating a hole through which the spinal cord runs. This locks the fragile spinal cord inside and provides protection.

On this arch are a few processes; little spikes that stick out like the needles on a porcupine. A Spinous Process points out posteriorly. The subcutaneous tip is the only part of the vertebrae that makes an appearance on the surface body.

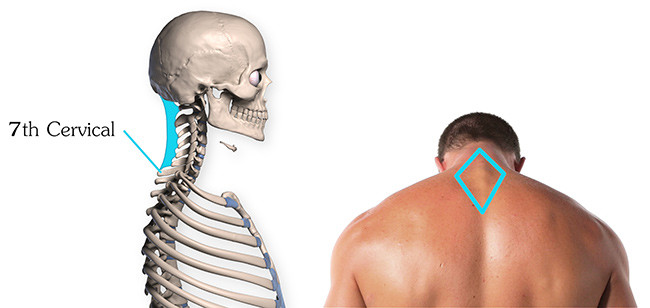

The shape and angle of the spinous process changes as we move down the spine. Cervical spinous process fans out like a lobster tail. Thoracic is a long spike. Lumbar is like the blade of an axe. But these shapes are not observable on the surface. We can only observe that the thoracic are pointy and the lumbar are longer. The first 6 cervical aren’t visible at all. Those are deeper in the neck, cover by the nuchal ligament.

The first visible vertebra is 7th Cervical, which is considered a major landmark of the body. This is the most pronounced and clearly visible vertebra along the spine, seen right in the the middle of this diamond shape between the trapezius muscles.

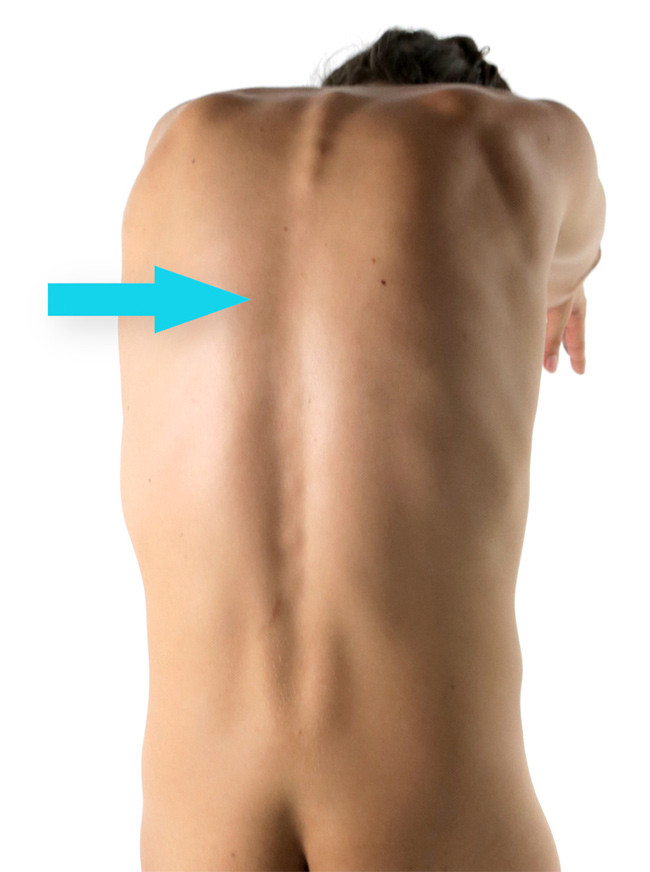

Also, the middle vertebrae of the thoracic section are usually not visible, even during forward lean, when the back muscles are stretched. But, this varies. Sometimes you’ll see all the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.

Motion

What the spine does, affects the entire torso. The thoracic section leans back, and the sacral leans forward. Since the rib cage and pelvis attach to the spine, they inherit this lean. So, the default position is curved, not straight and stiff. From there each section has it’s own range of motion.

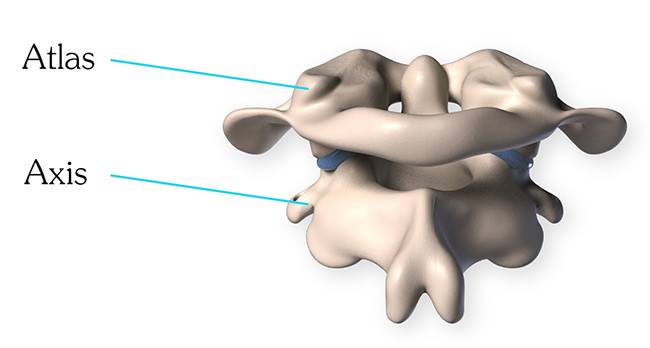

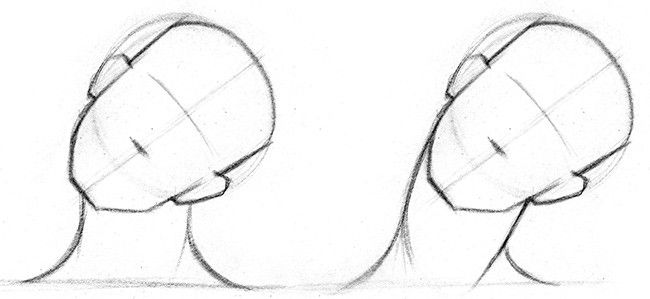

The cervical spine is the thinnest and most delicate, so this allows for more flexibility in the neck. Rotation along all 3 axes is possible. Flexion, extension, lateral bending and rotation.The first 2 vertebrae of the cervical section are unique. The Atlas and Axis. The axis has a vertical cylindrical process inserting into atlas. Can you guess what kind of joint that creates? You guessed it! A pivot joint. As we’ll see in a few minutes, this allows the head to rotate left and right.

50% of cervical rotation is at the joint where the atlas meets the axis. 50% of cervical flexion and extension is at the joint where the altas meets the skull. So, the head can rotate side to side and up and down without much help from the rest of the neck, but the head can’t bend laterally. The neck does that.

Let’s review. The cervical section is somewhat separate from the rest of the spine. It moves the head around and has a lot of freedom to move in all directions. The thoracic and lumbar sections are more limited and have to work together. Thoracic takes care of most rotation and lumbar takes care of flexion, extension and lateral bending.

Drawing the spine

Ok all that information is great and all.. But how do we actually draw this stuff. How does this apply to drawing the figure? Go to the next lesson to find out.