Bones of the Leg

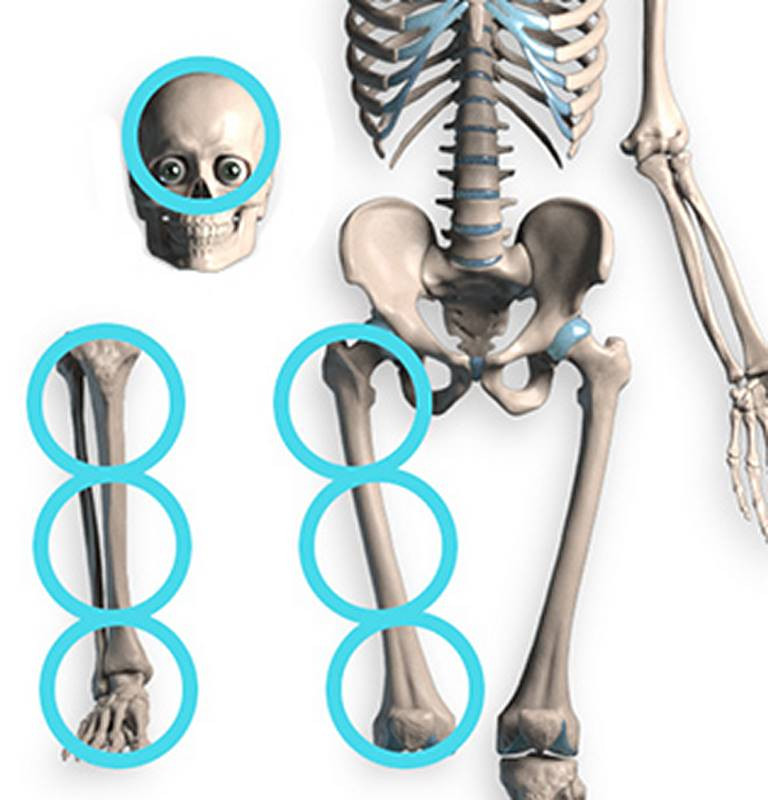

We studied the anatomy of the torso, we studied the anatomy of arms. Now, it's time for the legs! As usual, we'll start with the bones, so we can build our figures from the inside-out.

The legs have a tough job. They have to support the weight of the body, run, jump, kick and balance. Artists also have a tough job. If you struggle drawing the proportions, forms and important features of the leg bones, this lesson will help.

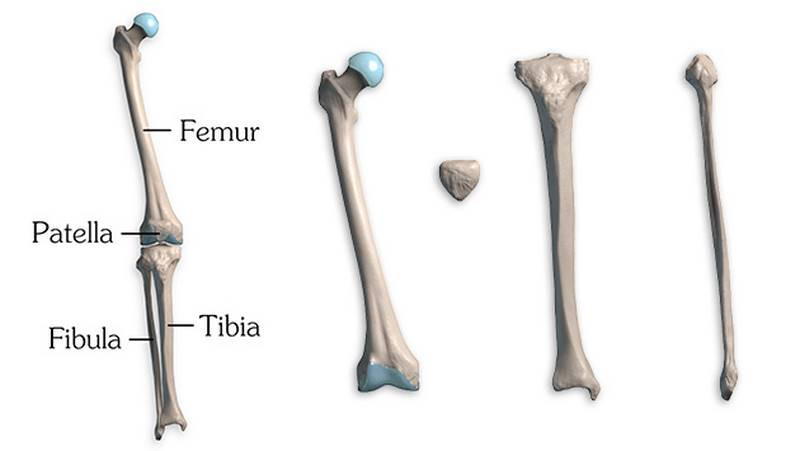

We'll go over the four leg bones: the femur, the patella, the tibia, and the fibula.

Femur

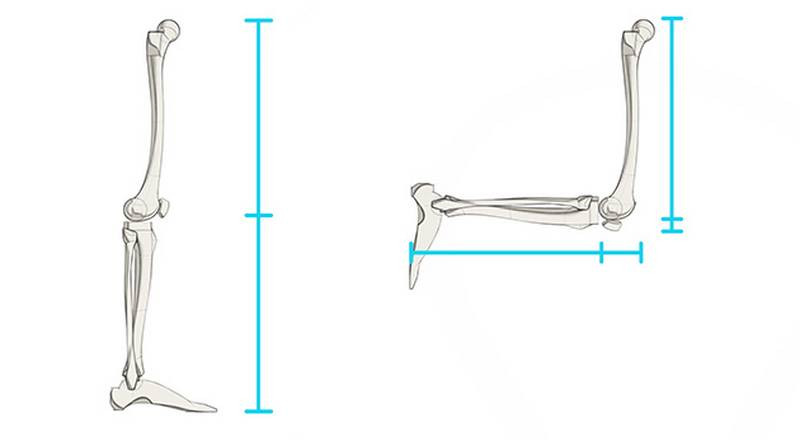

The femur is the strongest and longest bone in the human body. It makes up a quarter of your total height. In cranial units, the femur is three cranial units long. That's one whole cranial unit longer than the humerus! By the way, the lower leg is also three cranial units long, if you include the foot. For a quick proportion cheat, divide the standing figure in half. The top part over here falls right on that halfway point. Split the lower measurement in half again, and you know where the bottom of the knee needs to be.

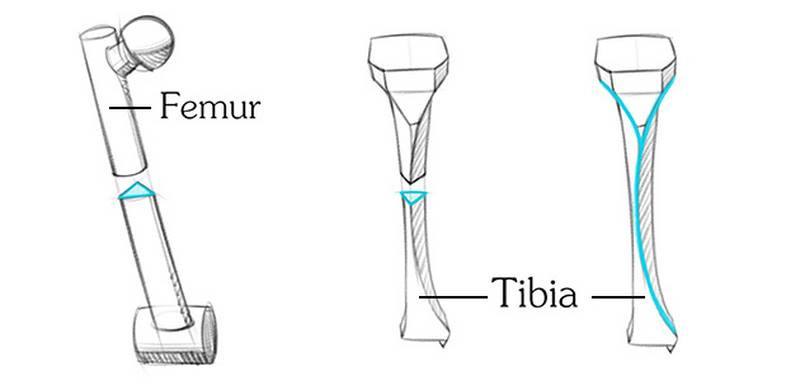

The femur is divided into the head, neck, body, and condyles. The simplified version looks like this: a spherical head, a diagonal neck, a long body, and a spool for the condyles. Let's start with the head.

The head of the femur is like an ice cream scoop by an employee who didn't care: off-center and deflated.

It pops into the acetabulum of the pelvis. Because it's a ball-in-socket joint, the femur can rotate in any direction.

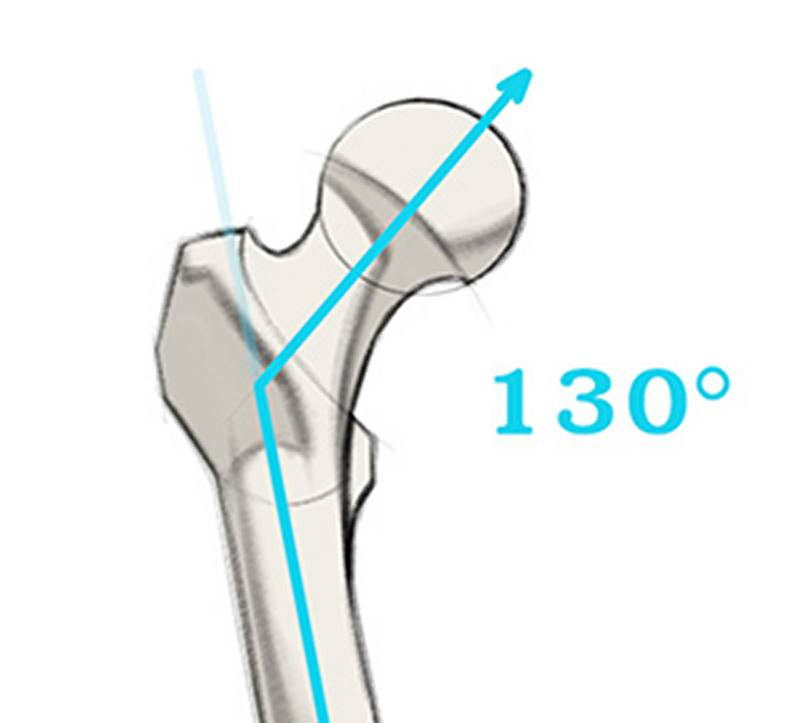

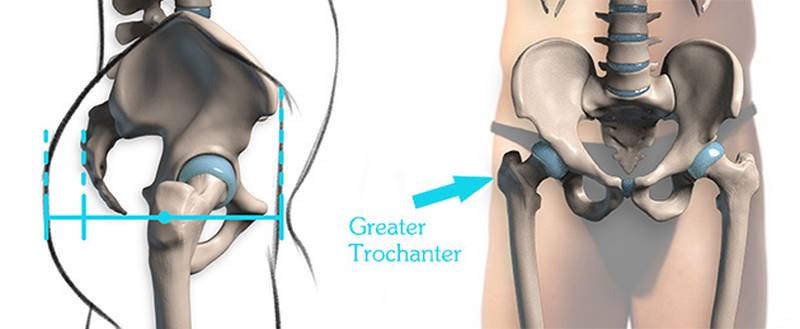

The neck connects it back to the body, at an angle of roughly 130 degrees. If you feel your hip, you can feel a bony part around that joint. What is that? Well, I'm very excited to introduce one of our greatest bony landmarks: the greater trochanter!! Everyone I know just calls it the great trochanter. Whatever, doesn't matter... The great trochanter is on the body of the femur, opposite of the head. It's like a big lever that sticks out to make the most lateral point of the femur. You can easily see it on the surface. Since it's subcutaneous bone, it will appear sometimes as a protrusion and sometimes as a depression when muscle bulge out around it.

The great trochanter is halfway down the body, at the level of the pubic symphysis. That's what I was talking about with the “proportion cheat” earlier. In side view, the great trochanter sits towards the front of the body… But once you add the butt, the great trochanter is right in the middle again! Of course, it depends on the size of your butt… Either way, it's a great reference point. It's even the widest point of the hips on many male figures. Though, most female figures have more fat sitting below the great trochanter, and that will be the widest point.

The great trochanter is pretty great, but that's not how it got its name. It has a sibling, the lesser trochanter. The two are connected through a crest. But the lesser trochanter is covered up by muscles so we artists don't really care about him!

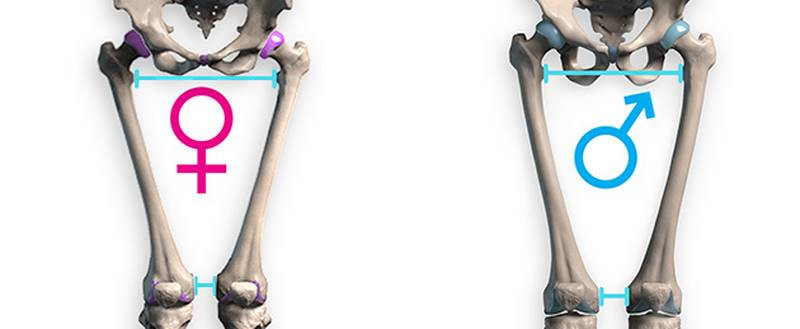

Let's keep going down the body of the femur. Notice the diagonal angle of the femur: roughly 175 degrees. Watch out! Artists who draw the femurs vertically kill the dynamism of the skeleton. Think about it this way: the femurs are separated by the entire width of the pelvis up top, but then they run inwards so they almost touch at the knee. Of course they're diagonal. But the angle won't always be exactly 175 degrees. That's just in the neutral anatomical pose. You can spread your legs, but the lower leg bones will follow. Also, it'll be an even sharper angle on females, because a female pelvis is wider.

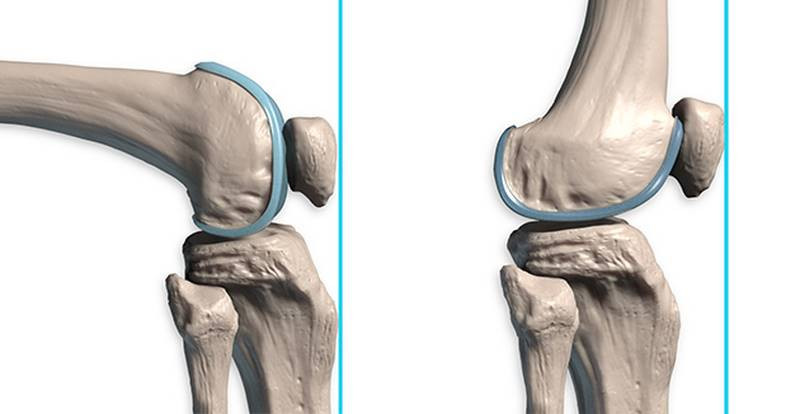

When viewed from the side, the femur has a cool space-saving design. It curves forward, so that when the leg bends, there's still room for the hamstring and calf muscles between the upper and lower leg.

Finally, we get to the distal end. This is the largest part of the femur. It's kinda similar to the design of the humerus from the arm. Remember that hammer shape of the epicondyles? The Femur has those bumps sticking out to the sides too. They're also called epicondyles. The humerus has a little bowtie and ball to articulate with the forearm. The femur has two giant wheels. Two big condyles that stick off the back. Not epicondyles.

The wheels are just “condyles”. Which makes sense because “epi” means above! I've found that most artist just call the entire wheel a condyle. Unless you're a doctor performing knee surgery, who cares! As long as you can draw it! When the knee bends, the femur rolls back on these wheels.

The axis of the condyles is horizontal. So the diagonal body of the femur meets them at an angle.

That middle groove is basically a track for the kneecap. You see, normally, the kneecap rests against this anterior part. But when the knee bends, the femur rolls backwards, and the bottom of the femur becomes the front. The kneecap slides through the groove. It always stays in the groove, like a ball on a track.

Patella

That's a fancy name for the kneecap. It's flat and shaped like home base. It has a ridge on its back that locks it into the groove between the condyles, helping it stay on those tracks. We'll have a separate premium episode devoted to the knee, and you'll learn all about it.

Briefly, it sits inside the quadriceps tendon and connects it to the front of the tibia by way of the patellar ligament. It help the quads pull the tibia forward during extension.

When your doctor does that reflex test, he taps the patellar ligament, which triggers the quads, which straightens the leg.

Normally the patella is the most anterior point of the leg bones. But when the knee bends, the patella shifts backwards slightly, and then the front edge of the tibia sticks out the most.

Tibia

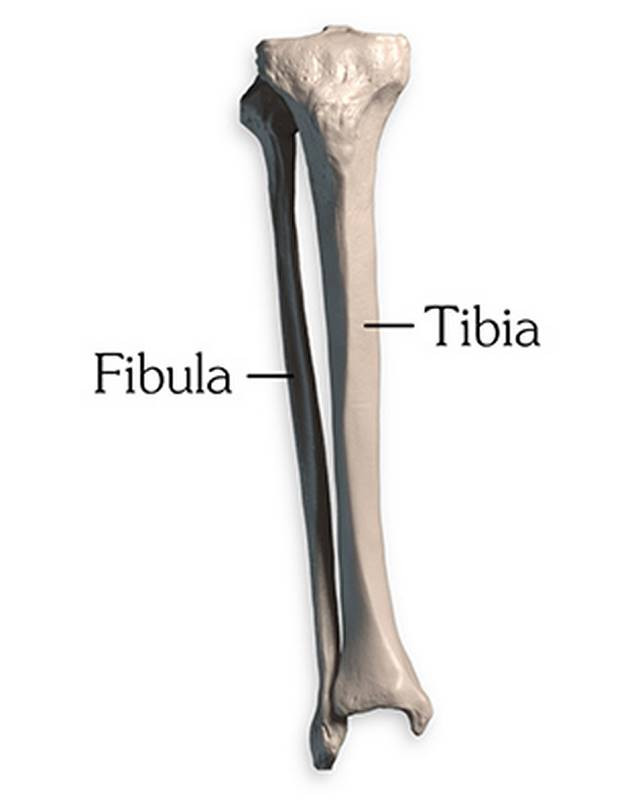

Ever get kicked in the shin? That's your tibia! The tibia is a big, tough bone that bears the weight of the body, so the fibula can take it easy. Which is good, because the fibula is tiny and weak. It's only as thick as your pinky finger! If it helps you remember, think “tough tibia and fragile fibula.”

Remember how the cross section of the femur was a triangle pointed backwards? The tibia's cross section is a triangle pointed forwards. It's that front edge that you see on the surface of the leg. The tibia creates a nice, flowing S-curve on the shin. On the surface, the top portion of the S curve stands out more when the tibialis muscle is included. But there's another larger rhythm to look for. A C curve from the inside of the knee all the way through to the inner ankle. That's the one I usually start with when drawing the lower leg.

The tibia is top-heavy with its knee end much bigger than its ankle end. Its thinnest point is about 2/3 down.

That front edge is only one of the five subcutaneous areas on the tibia. The other areas are the ankle, the outside of both condyles, and the tibial tuberosity where the patellar ligament attaches. The tibial tuberosity is the most anterior point on the tibia. It's easy to mistake it for the patella. We'll go into more detail about the knee in the next premium episode...

Something interesting happens with proportions when the knee bends. It creates an illusion where the upper leg and the lower leg look longer. The femur is the upper leg, the tibia is the lower leg. But when the leg is bent, you're measuring all the way out to the tibial tuberosity for your “upper leg measurement.” And when you measure the lower leg, you're including the width of the femoral condyles! Keep that in mind when you're measuring proportions.

Okay, back to those tibial condyles. The tibia has a wide top plane, shaped like the letter D. It hangs off the back of the body. It's separated into medial and lateral platforms, for accepting the femur's medial and lateral condyles. But they aren't as concave as you would expect. They're actually kinda flat. The femoral condyles sit on this plateau. So the knee is an imperfect hinge joint that allows flexion, extension, and some rotation. If this seems like an unstable design to you, it kind of is! But there's lots of strong muscles, tendons, and ligaments that hold the joint together.

Now let's talk about that fibula.

Fibula

The fibula sits entirely underneath the knee joint. It's under, behind, and lateral to the tibia. Its job is to add structural support in the ankle and additional attachment space for muscles. There are two tibio-fibular joints that allow it to wiggle around adding some flexibility within the lower leg, but you can't really see this movement on the surface. There's one plane joint where the fibula connects with the tibia's lateral condyle, and another at the ankle.

This distal end actually hooks around one side of the ankle. Together with the tibia, they grab onto the foot like a wrench. Or like a unicycle. And like a unicycle, the wheel on the foot rotates inside this joint to dorsiflex and plantarflex the foot.

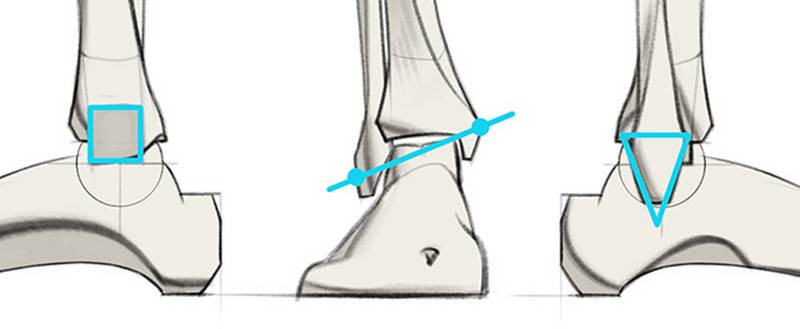

The fibula continues down lower than the tibia.

Make sure to look for this angle to make the inner ankle higher up than the outer ankle for a more dynamic design. Don't draw symmetrical ankles. Not only is it anatomically incorrect, it's boring!

Also, the shapes of the bumps are different. The fibula has a pointed diamond shape, while the tibia is blocky. I'll give you more tips for how to draw the ankle in an upcoming lesson, on the Bones of the Foot. But the next lesson will be a special premium episode on the knee by super-special guest instructor Marshall Vandruff.

Assignment

Your assignment is a 2 parter. For the first part you can use the skelly app to pose the leg bones, or just use the images I provided in the downloads tab. Draw the leg bones as simplified forms. Don’t copy the contours, study the form and break it down to geometric forms that you can remember.

I’ve also provided some leg photos of models. Do anatomy tracings over those to find the leg bones. Look for subcutaneous landmarks to figure out where the bones go. Try to do both of these exercise on your own, before I post my answer videos.